Lucile Lloyd

A Life in Murals

During the Great Depression, Lucile Lloyd (1894-1941) built an active career as a mural decorator. Her colorful scenes and stenciled patterns adorned the interiors of numerous homes, schools, restaurants, shops, and public buildings throughout the Los Angeles area. Lloyd lived and worked at a time when murals were at a height of popularity. Hand-painted ornament was fashionable in homes and public buildings alike, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided government funding for public murals to ease unemployment during the Depression. In 1935, Lloyd became the first woman artist in Southern California to receive a prestigious WPA commission. The resultant mural, California’s Name, was her last major project. Since Lloyd’s death in 1941, many of her works have been lost. Drawn from the Lucile Lloyd papers at the University of California Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collection, Lucile Lloyd: A Life in Murals provides a rare look at a prolific but understudied artist.

Lucile Lloyd was born into a family of artisans and began her training at an early age. Her grandfather, Jacob Lloyd, was a designer who supplied large mills in England and France with textile and wallpaper designs. Her father, Harry K. Lloyd, was a textile and stained glass designer who worked for Monadnock Mills in New Hampshire, one of the largest manufacturing complexes in the northeastern United States. Alfred Godwin, a well-known Philadelphia stained glass designer, was her uncle.

Lloyd apprenticed in her father’s studio from the ages of eight through nineteen. She created many designs for stained glass, though few were realized. Lloyd attended the Woman’s Art School at Cooper Union from 1913-19, and the Art Students League in 1916 and 1917. After graduation, she worked in the drafting rooms of the New York architectural firms of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill and of Bertram Goodhue. In 1919, Lloyd relocated to Southern California, where she established herself as an independent muralist.

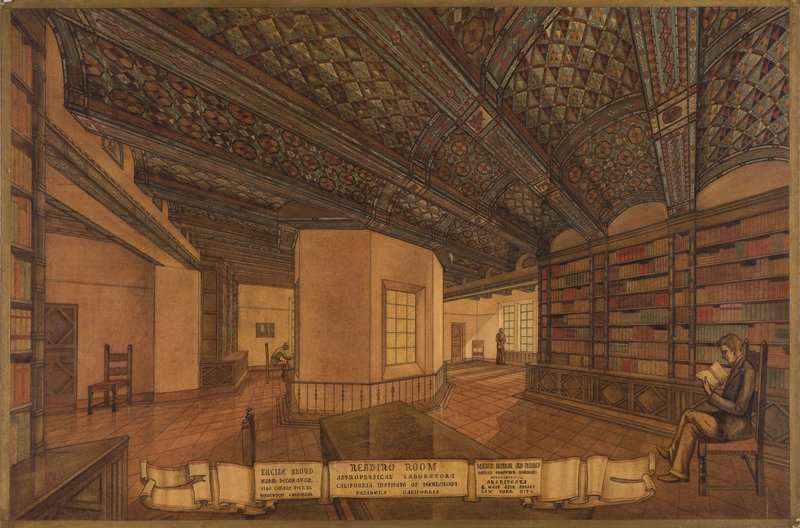

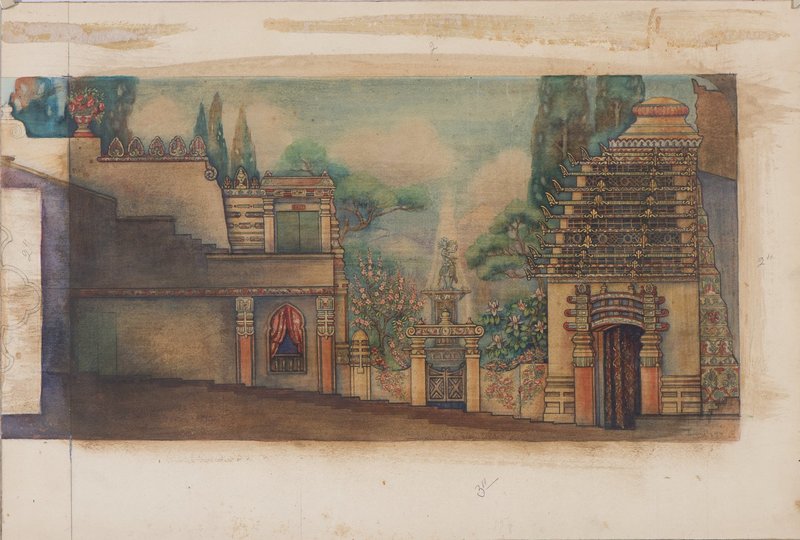

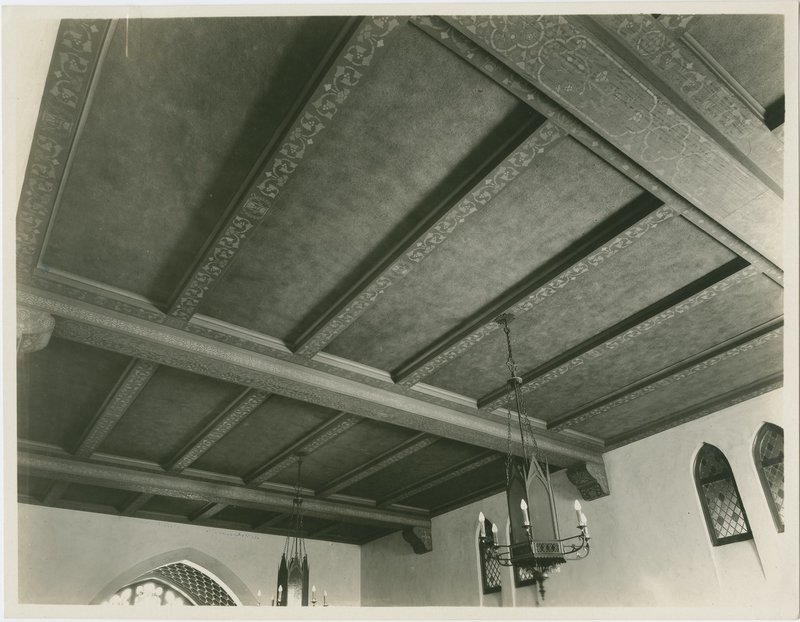

The trade of mural decoration, as practiced during Lloyd's time, required a range of skills in art, craft, and design. Muralists were called upon to create large-scale scenic paintings, and to stencil decorative patterns on ceilings and walls as architectural embellishments. Projects were often commissioned by architects. Lloyd's ability to read and produce architectural drawings, therefore, was crucial to her success. Lloyd’s papers include a number of scale drawings for murals, and perspective renderings of proposed projects that were intended to convey to clients the final look of a decorative scheme. In painting historical or literary subjects, she dedicated large amounts of time, sometimes months, to researching her subject matter.

"Very few realize the scope of a mural painter's work. He must not only paint but he must model, carve, make renderings and models to scale and full size working drawings. He must have a good working knowledge of architecture and construction and understand the preparation of wood, plaster or cement for decoration."

-Lucile Lloyd, "The Relation Between Architecture and Decoration,” 1925

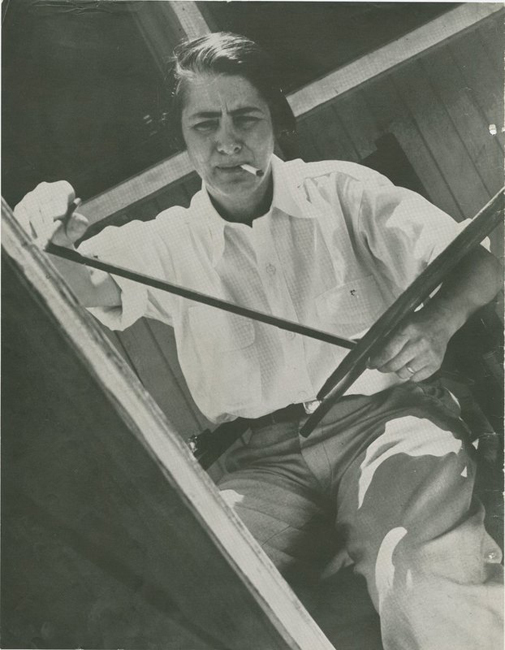

During Lloyd's time, mural painting was largely the domain of men. As was typical of the era, the Los Angeles press reported on Lloyd's projects in terms of her gender. Newspaper articles she clipped and saved voice amazement that such large and complex works were created by a woman. For instance, a Hollywood News article titled "Large Homes Decorated by Woman Mural Artist," notes that Lloyd climbs scaffolds in menswear "without handicap," and that her sweater sets off the blue of her eyes. Another writer portrays her as a rebellious character with a distinctly un-feminine disregard for etiquette and manners. The article features a photograph of Lloyd engrossed in painting, cigarette pursed between her lips, seemingly disinterested in what viewers would think of her or her work. But as Lloyd's professional papers show, unconcern is far from the attitude with which she undertook her career. Employers described her as "businesslike," "painstaking," and "prompt." Lloyd's own writings show that she believed mural decoration should be tailored to the interests of clients.