J.R. Davidson: A European Contribution to California Modernism

This is a digital version of the exhibition which was held in Fall 2019 at UCSB's Art, Design & Architecture Museum.

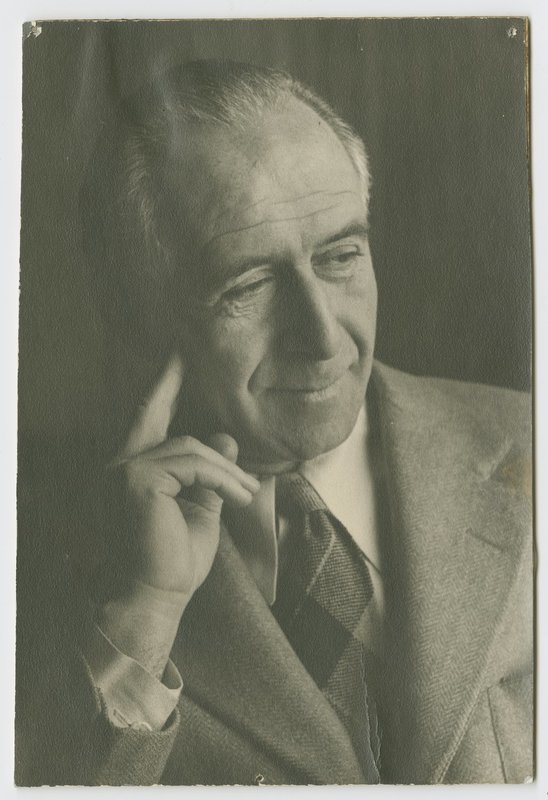

J.R. Davidson (b. Germany, 1889-1977), architect of the Thomas Mann House (1914), and three prototypes for the Case Study House Program (1946-48), contributed his European background, and specifically his training in interior design, to the advancement of modernism in Southern California. Throughout his five decades long career, Davidson produced an architecture highly functional in its plan, yet sensitive to its natural surroundings in its elevations. Despite the achievements that Davidson attained in his professional life, he remains an understudied figure in the history of modern architecture. This exhibition, organized with materials from the architect's archive at the Architecture and Design Collection of the AD&A Museum, fills this gap by highlighting those aspects of Davidson's trajectory that were unique to his way of understanding architecture and its practice. These include, for example, the way Davidson conceived architecture from the inside out and the integration of the outside in through large-scale windows. Photographs, notebooks, manuscripts, and drawings document, in the exhibition, the prolific career of the German emigre bringing it to a new standing and recognition.

J.R. Davidson, A European Contribution to California Modernism is curated by architectural historian Lillian Pfaff, who is also the author of the illustrated book on Davidson.

“For a house, I want to achieve serenity and cheerfulness. Most people value these in a house, but few clients understand the plan’s features which produce them. Serenity is achieved through an order. The continuous line is the restful one” (J .R. Davidson).

“J. R. Davidson searched for the ideal floor plan, which expanded the life within. His innovations often produced a loose-fitting envelope around a perfect floor plan” (Esther McCoy).

Julius Ralph Davidson (b. Germany, 1889-1977) has been largely overlooked in architectural history, overshadowed by his contemporaries Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Despite his important contribution to California modernism, it has not been easy to place him in the pantheon of mid-century architects. Yet, architectural historian David Gebhard called Davidson “the one designer in the thirties who most elegantly brought the European modern and California styles together,” while Reyner Banham, the noted British architectural critic and writer, described him as “ingenious and underrated.” Ironically, the one project that Davidson is well known for, the Thomas Mann House, in Pacific Palisades, was not one of which he was particularly proud—supporting the view that his ideas and intentions have not been properly appreciated and understood.

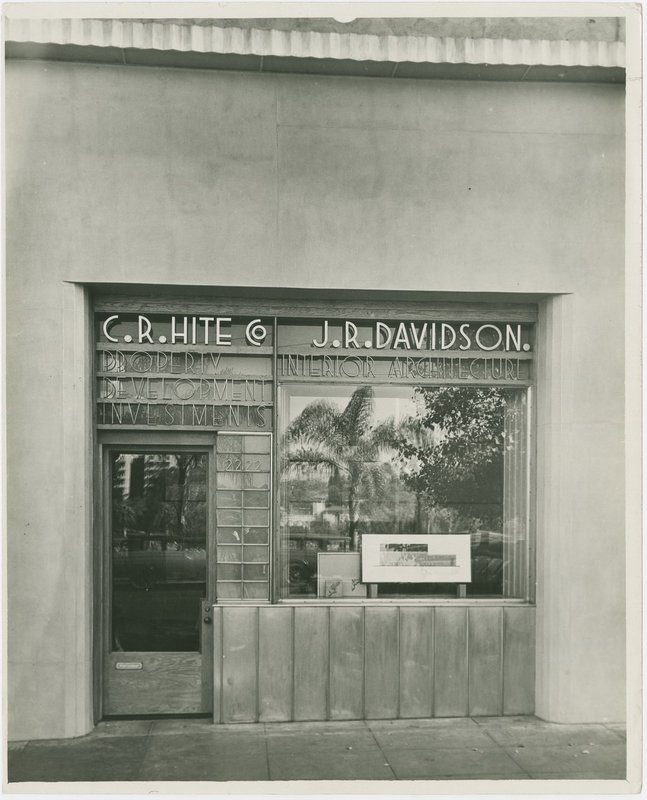

A German émigré, J. R. Davidson arrived in Los Angeles at the end of 1923. Although he had no formal architectural training, he had undertaken apprenticeships in furniture and interior design in Berlin, London, and Paris, and, drawing on this experience, he began to make a name for himself in the design of retail stores, bars, and restaurants. Davidson’s interiors are characterized by a choice of colors and materials reminiscent of the Art Deco movement in Paris, and a distinct and unique use of indirect lighting, and customized lamps.

From the 1930s through the 1950s, Davidson focused on the design of residential homes. In Los Angeles, he designed three houses for the experimental Case Study House Program (CSH #1, #11 & #15), each distinguished by their efficient layout. He was the only contributing architect to develop a replicable prototype, the original idea of the program.

Over his lifetime, Davidson produced more than 150 buildings and projects, working variously in the International Style, and later taking a more moderate modern approach by adapting such regional building types as the ranch house. Typical of his houses—still of timeless elegance—is a smooth transition from interior to exterior, as well as dedicated private indoor and outdoor spaces for each resident. His projects were frequently written up in such publications as Arts & Architecture, The Architectural Forum, Sunset Magazine, Architect & Engineer, and The Los Angeles Times.

So, why is J. R. Davidson’s work forgotten? The answer is multi-faceted. Principally, he was not a licensed architect, meaning that he could not access large-scale public projects that would have brought him recognition. He worked alone, with occasional help from his wife, Greta, and son, Tom, and never developed a large architectural practice. A reserved man, he was not motivated by self-promotion, as were some of his peers.

At the heart of his work lies his interest in architectural details which resulted in a focus on the interior. His main concern was to meet his clients’ briefs, to solve their unique problems, and to address the ways in which they wanted to live. His houses were designed from the outside in, putting less emphasis on the facade. This approach lent itself to a flexibility of style. Davidson adapted to regional variations and materials without changing his spatial solutions, which were always oriented around the view of the landscape, the light, and the privacy of each inhabitant